Home  Types of source Types of source  18th-century 18th-century  Women's distinctive vocabulary Women's distinctive vocabulary

|

| Eighteenth-century Dutch kitchen interior. Source: Jane Austen's World. Click on the image to see an enlarged

version.

|

'The Distaff or the Kitchin': vocabulary relating to domestic and household

matters

Once women began to write and publish in significant numbers at the end of the seventheenth

and beginning of the eighteenth century, it was repeatedly commented - by both male and

female writers - that such activity was in competition with women's proper sphere, namely

the domestic household: sewing, cooking, and household management in general. Initiating a

correspondence with the philosopher John Norris in 1693, Mary Astell asked him to take

notice of her literary endeavours notwithstanding her departure from more appropriate female

employment:

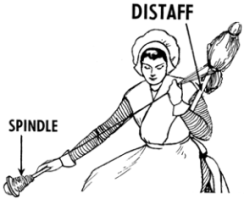

Sir though some morose Gentlemen wou'd remit me to the Distaff or the Kitchin,

or at least to the Glass and the Needle, the proper Employment as they fancy of a woman's

Life; yet expecting better things from the more Equitable and ingenious Mr Norris, who Is

not so narrow-soul'd as to confine Learning to his own sex, or envy it in ours, I presume to

beg his Attention a little to the Impertinencies of a Woman's Pen... (Norris 1695: 1-2; for comment and context see

Perry 1986: 73ff.)

|

| Source: Wikipedia. Click on the image to see an enlarged version.

|

In 1710, the Tatler poured scorn on Astell's 'Scheme of a College for Young

Damsels', using much the same imagery to make the point that women should stick to their

own territory rather than usurping male provinces:

instead of Scissors, Needles, and Samplers; Pens, Compasses, Quadrants, Books,

Manuscripts, Greek, Latin and Hebrew are to take up [the women students'] whole Time. (Steele 1710: vol. 2, p. 199;

see Perry 1986: 229)

The perceived opposition between proper female domestic employment and intellectual

activity, particularly writing (or, in Astell's words, 'the Impertinencies of a Woman's

Pen'), continued strong throughout the eighteenth century (for examples of some typical

attitudes see Jones 1990:

chapter 4, 'Writing', pp. 140-91). Years later, Jane Austen's brother James felt he had to

justify his sister's labours by defending her against any imagined implication that she had

neglected the housework. In verses composed shortly after her death in 1817, he wrote:

They [her family] saw her ready still to share

The labours of domestic care

As if their prejudice to shame;

Who, jealous of fair female fame

Maintain, that literary taste

In women's mind is much displaced;

Inflames their vanity and pride,

And draws from useful works aside.

|

|

| Two examples of satin stitch. Top: goldwork: satin stitching in gold thread on cloth of gold. Courtesy of Mary Corbet's Needle 'n Thread. Bottom: satin stitch and 'skinny' cording. Courtesy of Gabriel Amaya at House of Embroidery. Click on each image to see an enlarged version.

|

Readers are assured that Austen did not stint on her useful works, the domestic labours

proper to women, and it is these James sees as manifesting 'Her real & genuine worth',

'Her Sisterly, her Filial love' (for full text of poem see Selwyn 2003: 86-8; it is also

reproduced online here from Southam 2002). (Austen afficionados will

remember that Leslie Stephen particularly noted the writer's domestic accomplishments in

his DNB entry of 1885: 'Jane learned French, a little Italian, could sing a few

simple old songs in a sweet voice, and was remarkably dexterous with her needle, and

"especially great in satin-stitch"'; Stephen takes his

information from J. E. Austen-Leigh's Memoir of Jane Austen and Other Family

Recollections, published in 1871, pp. 71, 77.)

For historians, whether literary or linguistic, this is a contentious and difficult matter.

Should we celebrate the importance to women of domestic matters, thereby running the risk of

keeping them shut up in the kitchen, or should we be suspicious of the urge to demonstrate

links between women and domesticity, thereby running the risk of ignoring one of the few

areas of activity in which they had the chance to excel?[1]

Whatever the right answer to this question, the close correlation claimed, and - as Astell's

letter shows - often resisted, between women and domesticity is in some instances strikingly

confirmed by the OED's citation sources for such vocabulary. If we look at the

quotations for one of the few female authors cited in large numbers in OED1, Jane

Austen (around 700 in total[2]),

we find a remarkable prevalence of words to do with domestic or household matters, e.g.

- beaver ('a particular kind of glove')

- butler's pantry ('a pantry where the plate, glass, etc., are kept')

- cousinly

- consequences (the game)

- spot ('a spotted textile material'), etc.

Burchfield's twentieth-century Supplement added nearly 350 more quotations from Austen, in

which the same characteristic dominates even more strongly, e.g.

- baby-linen

- baker's bread

- bath-bun,

- black butter (i.e. 'apple-butter')

- bobbinet ('A kind of machine-made cotton net, originally imitating the lace

made with bobbins on a pillow')

- brace ('One of a pair of straps of leather or webbing used to support the

trousers; a suspender')

- china crape

- china tea

- coffee urn

- corner shelf, etc.

|

| Title page of Hannah Glasse's The Art of Cookery (1774)

taken from Google Books. Click on the

image to see an enlarged version.

|

Some other female writers, for example the seventeenth-century writer Hannah Woolley (c. 70

quotations) and the eighteenth-century writers Hannah Glasse (c. 400) and Elizabeth Raffald

(c. 270) are cited almost entirely for domestic cooking terms taken from their books on

cookery and housewifery. The same is occasionally true for male writers too (e.g. J. Knott,

quoted around 70 times for culinary terms from his Cook's & Confectioner's

Dictionary of 1723).[3]

In general, the explanation for the female provenance of the

quotation sources for such vocabulary must be that domestic and household matters were often

a matter of discussion or responsibility for female writers rather than for male. But it may

also be the case, given prevailing assumptions about women's roles and women's

characteristic subjects of interest, that the OED lexicographers were more likely

to pick up on such vocabulary in female- than in male-authored sources. To clarify this

question we need to carry out more research into both source texts and the OED

itself.

Several further points of interest arise:

(i) Many of these domestic terms in Austen's writing - including all those quoted above -

are also first quotations in OED. This is a notable feature. In

particular, of Burchfield's 350-odd additions of Austen quotations to OED in the

twentieth-century Supplement, about half are first quotations. Was Austen really the first

person to use these terms in print? or does OED cite them from her work simply

because this was relatively thoroughly combed by the lexicographers and readers, i.e.

OED was more likely to find such vocabulary in Austen than in other less well known

sources? (and also, as suggested above, that readers and lexicographers would have a prior

expectation that texts written by women were a good source for such terms?) Again, we need

to read and research further to try to establish an answer to this question.

(ii) Notwithstanding OED's comparatively thorough treatment of Austen, the readers

or lexicographers on occasion still overlooked such terms in her writing. Sometimes they

went altogether unrecorded, e.g.

|

| Music and (somewhat illegible) instructions for the Boulanger

('baker') dance. Source: Jane Austen Information

Page. Click on the image to see an enlarged version.

|

- Boulanger (a dance): in Pride & Prejudice, 1.iii.13, Mr Bingley

danced 'the two sixth with Lizzy, and the Boulanger'; the term crops up again in the

Letters (5 September 1796; Le Faye 1995: 8), 'We dined at Goodnestone,

and in the evening danced two country dances and the Boulangeries')

- family party: as in Pride & Prejudice, III.xviii.384, 'The comfort

and elegance of their family party at Pemberley'

- netting silk: as in 'There were no narrow Braces for Children, & scarcely

any netting silk' (letter of 27-28 October 1798 from Austen to her sister Cassandra, Le Faye 1995: 75).

OED3 draft entry June 2008 lists several sewing-related compounds for

netting (n.3, s.v. C1), e.g. netting-cord, -cotton,

-needle, etc., but misses this one

- out of place ('without a place or situation', said of a domestic servant): as

in 'I believe I could help them to a housemaid, for my Betty has a sister out of place',

(Sense & Sensibility, III.i.260). Cf. OED3 draft entry June 2009 s.v.

place, 14a: 'A job, office, or situation'; the Dictionary does not recognize the

phrase 'out of place'. The phrase is used by both Good Mrs Brown and Rob in Dombey and

Son, XVII.lii (p. 775 in Oxford Classics edition), 1848: '"You're not out of

place, Robby?" said Mrs. Brown in a wheedling tone. "Why, I'm not exactly out of

place, nor in," faltered Rob. "I - I'm still in pay, Misses Brown."'

- working candle ('candle for working [e.g. sewing] by'), as in 'I hope it won't

hurt your eyes - will you ring the bell for some working candles?' (Sense &

Sensibility, II .i.144)

Alternatively, the terms were sometimes recorded in OED, but Austen's prior use was

missed: e.g.

- lottery (the card game), mentioned in Pride & Prejudice, I.xvi.84

(first published 1813) but dated from 1830 onwards in OED.

Or occasionally what was missed was an example of usage which supplied valuable additional

evidence for a term under-represented in OED's quotation record:

- satin-stitch: 'I beleive I must work a muslin cover

in sattin stitch, to keep it from the dirt' (letter of 17-18 January 1809 from Austen to her

sister Cassandra, Le Faye

1995: 165). OED records only two examples of this term, from Hannah Wooley's

work on household management, Supplement to The Queen-like Closet, dated

1684, and Fanny Trollope's novel The Widow Married of 1840: Austen's instance

usefully bridges the 156-year gap between these two quotations.

(iii) Similarly, domestic and household vocabulary in other eighteenth-century female

writers was also occasionally missed by OED, even in writers whose work they read

and quoted from relatively intensively, e.g.

- Wortley Montagu's use of the term brass: 'he proffers to...see to get Pewter

and Brass as much as you will have occassion for' (Halsband 1965: vol. 1, p. 193). OED2

recorded the definition 'Pewter utensils collectively; pewterware' for pewter but

has no analogous definition for brass

- The same writer furnishes an antedating for the term braziery, to mean 'brass

household equipment of various sorts', in a letter of 1713: 'you have plates hir'd for 5s.,

and other Pewter at the rate of one d. per pound. But we are like to have a good deal of

trouble to get Brazerie' (Halsband 1965: vol. 1, p. 195);

OED1/2 does not recognize the specific household application and defines simply

'Brazier's work', with a first quotation of 1795

- Seward's use in a letter of 1790 of winter-room, a combinatorial form which

OED records only from 1911: 'It is the pleasantest winter-room in the house, where

many are pleasant; - but the sun looks on this at noon, and gilds it on through the winter

day' (1790; Constable

1811: vol. 3, p. 37).

(iv) Finally, such terms are sometimes recorded but with insufficient information to be able

to understand the implication of their usage. An example is:

- thread-satin, listed in OED1/2 without comment as a combinatorial form

of thread, with a quotation from the London Gazette of 1713 ('A Thread-

Sattin Night-Gown, striped red and white'). Wortley Montagu writes in a letter of 1721, 'I

have taken my thread satin Beauty into the house with me. She is allow'd by Bononcini to

have the finest Voice he ever heard in England' (Halsband 1965: vol. 2, p. 13). As Halsband's

notes tell us, the reference is to Anastasia Robinson (d. 1755), 'prima donna', closely

associated with Bononcini. Wortley Montagu's use is clearly figurative but what does

thread-satin mean? Is she referring to the (poor-quality?) dress material Robinson

wore, or intending some reflection on the singer's voice or her character?

Footnotes

[1] See further Macheski 1986.

[2] Our graph of Top female sources in Initial results represents Austen's quotations as over

1,000 in all. This is because the data for the graph is taken from electronic searching of

OED2, which combines OED1 with Burchfield's Supplement. EOED has since

searched the Supplement manually and discovered that Burchfield was responsible for adding

around 350 of the OED2 quotations, a matter to be discussed further on our Austen

pages here [under construction**].

[3] The quotations from Nott seem all to have

been added to OED by Burchfield in the twentieth-century Supplement, perhaps at the

prompting of Marghanita Laski.

|

|

Last Updated ( Wednesday, 17 March 2010 )

|

|

|

|